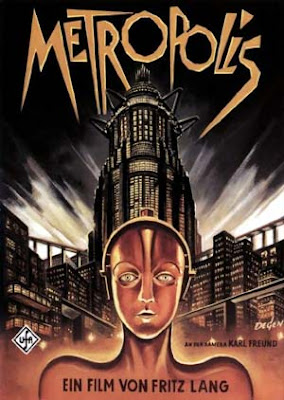

Metropolis is one of Fritz Lang’s most perplexing films. Throughout its eighty years of life, it has provoked diverse polemics and reactions from each generation that has watched it. Nevertheless, no matter the vantage point taken for its analysis, a recurring criticism, or observation, has been the disjunction between its visuals and its story, with the former supposedly greatly surpassing the latter in quality.

It cannot be denied that the special effects and visuals of Metropolis have a mesmerizing quality. The expensive budget and extensive time allocated to its production completely paid off in this regard. The city featured in the film, composed of imposing buildings and machines, is only part of the grandiose world projected by Metropolis. The meticulous attention paid to details was probably the cause of this success. For example, the movement of actors through the sets is synchronized so perfectly that they look either like machines or like chaotic waves, depending on the evolution of the story. The workers are one with the machines; they completely lose traits of individualism and psychological qualities. Their black uniforms, coordinated movements, and similar physiognomies and facial expressions make them amalgamate and become part of the mise en scène. According to Siegfried Kracauer, such “visual depiction of crowds [is] pleasurable to the eye but politically totalitarian[.] Lang’s geometrical forms in Metropolis deprive the masses of a will and reduce their public participation to a demagogic reflex.” In fact, even when the workers are apparently out of control by the robot Maria’s incitement, their movements are not so much willed by them as programmed and imposed by a greater force, in this case the robot, and thus by its master Joh Fredersen, here representative of the state.

Even if Metropolis is not scrutinized under the same political magnifying glass as Kracauer’s, the narrative behind its elaborate mise en scène is significantly lacking in quality and effectiveness. The film’s core message could not be more clichéd and simplistic: “the mediator between head and hands must be the heart.” This emphasis on the need for a savior becomes a call for inertia. The workers should wait for a magical solution to descend from the heavens and fix their problems. It becomes somewhat comical that the recommendation to rise against the oppressive machines in order to demand their rights would come from the robot Maria rather than the human one. Nevertheless, it is fairly insulting the minimal brain activity granted to the working class in Metropolis. They can be hypnotized and lured into either madness or lethargy with the same ease. These deliberate plot choices, however, might be a reflection of the society of the time. Thus, as Kracauer noticed, “Metropolis was rich in subterranean content that, like contraband, had crossed the borders of consciousness without being questioned.” For such a reason, Metropolis can be considered a document that records the social conditions that created the environment for the rise of the Nazis.

Metropolis is therefore valuable evidence and material when trying to perform an autopsy of the Weimar society. By dissecting this kind of document, both direct products and emblematic representation of the period, important aspects of its society are unveiled. This is true because, as Kracauer points out in “The Mass Ornament,” “the surface-level expressions, […] by virtue of their unconscious nature, provide unmediated access to the fundamental substance of the state of things.” Thus, Metropolis’ society, one whose individuals could only act and react as atom-like parts of a mass, is a startlingly close representation of the society that would soon cheer for Hitler’s indoctrinations as it was apparent in his propagandistic, yet documentary film, The Triumph of the Will. Adding to such a tendency for mimicry, society’s need and desire for a strong leader and savior is also a characteristic that Metropolis identified and addressed. The same blind admiration and devotion for both Marias can be identified in the footage from Hitler’s early rallies across Germany. Germans were going through a time of great depression and economic distress and needed a father-like figure who would reorganize the chaos they were in. Coincidentally, this is exactly what Maria was supposed to do in Metropolis. She is the connection between the workers and the mediator who would save and release them from the enslaving machines of the city.

Nevertheless, even if Thea von Harbou was able to transcribe the collective unconscious of the time, the romantic plot between Freder and Maria is trite and irrelevant. They fall in love after their first glance, and they declare such mutual love after only knowing each other’s names. Their kiss of celebration and triumph is completely extraneous to the flood that is threatening to destroy the future of the city, its children. Moreover, it seems that Freder is not, like Jesus, sent from the heavens as the prophet that the working class is waiting for, but is rather another marionette controlled by the intoxication of Maria’s seduction or love. Such development of the plot makes unmistakable the mark and influence that Hollywood’s box-office films had on Metropolis. Their asphyxiating cloud of romantic, unrealistic, and simplistic plots had finally reached the skies of German films.

In addition to such an unnecessary romantic subplot, as Tom Gunning puts it, “everyone hates the ending” to which it leads. It seems as if Lang and von Harbou had tried to assume Hollywood’s equation for profit maximization: an unrealistic happy ending. As it might be expected, Kracauer also finds such an ending objectionable. He criticized it as veiling its audience’s eyes with easy resolutions that would make them forget about the politically charged problems initially posed by the film. In this case, he points out that the apparent victory of the working class is only an illusion, part of Joh Fredersen’s plan to ensure his continuous domination over his city and over his son. By letting the workers become intoxicated with the idea of having won over the ruler and considering themselves at his same level, they will be back to lethargy, since there is nothing else to fight for. “[Joh Fredersen’s] concession […] amounts to a policy of appeasement that not only prevents the workers from winning their cause, but enables him to tighten his grip on them” (Kracauer). Therefore, the ruler’s influence is now exerted upon the worker’s hearts, making it even easier than before to manipulate them. Joh Fredersen’s plan goes beyond the domination of the city into his personal life. “On the surface, it seems that Freder has converted his father; in reality, the industrialist has outwitted his son” (Kracauer). He conveniently makes his rebellious son believe that he was finally worth something since his actions made the conciliation between the ‘head’ and the ‘hands’ of Metropolis possible. After believing in such a victory, Freder can rejoicingly return to his comfortable nest and stop contradicting his father.

It seems oddly simplistic to believe that the valid criticism raised by Kracauer would have passed unnoticed by someone with the mental sharpness of Lang and von Harbou; which makes one wonder whether such an ending was cynically constructed. This theory takes on greater weight when noticing that the workers are represented by Grot, “a management spy and informer, who cares only for the machines of Metropolis. And the heart is the boss’s son” (Gunning). Therefore, it becomes apparent that the ending’s facility might have been a way of appealing to both the mass audiences, who prefer compact endings, and to the intellectual niche, who would decode the criticism of the state in such absurd ending. Upon understanding the ironic final twist, one’s perspective of the film drastically changes. However, such interpretation is obscure and not easily recognized, and thus, the majority of its viewers would not walk away from the cinema thinking that the film’s final resolution is a criticism of the political system.

No comments:

Post a Comment